Frank Cimatu

JULIO, a 39-year-old seafarer, decided to go home to his hometown in Manabo, Abra just in time for their fiesta in March.

He said that he had been planning this for the past three years. So from his work base in the United Arab Emirates, he took the plane home.

Fred and his family were tired of spending White Christmas in the United Kingdom and decided to spend it in his hometown in Samoki village in Bontoc, Mt. Province.

As the practice among balikbayans, his friends asked him to bring their paw-it (gifts mostly in cash, medicines, and expensive items) to their relatives in the nearby towns in Mt. Province.

The government did not call our balikbayans and overseas Filipino workers heroes only because they pump back remittances to the local economy but also for what cultural scientists call the “culture of circulation” they bring to their hometowns.

This is more pronounced in Abra which has one of the highest number of OFWs in Northern Luzon, with seven percent of the provincial population said to be OFWs.

The provincial government has designated a Balikbayan Day in December, an OFW Day in May, and an Abra Provincial OFW Center in Bangued town to assist them. There are Miss or Mrs. Balikbayan in almost all the villages in Abra. In fact, the family of Julio has invited his townmates for a canao or a feast weeks before he even arrived.

The balikbayan culture in Bontoc is a bit different.

There is a word called “Nikimalika” which was coined more than a hundred years ago, decades before the Philippines started importing workers abroad.

Nikimalika means to “have been in America.” This was first used to describe the Bontoc warriors and women who were brought to the St. Louis World’s Fair in 1904, where they were displayed in Igorot villages and made to slaughter dogs and eat them.

Some of these Nikimalikas actually came and went with the fairs in the United States and brought dollars and items with them. These Nikimalikas were actually the first OFWs, or overseas cultural workers, to be exact.

Most of the balikbayans in Western Mountain Province tended to be health workers, pastors, and white-collar workers in the US and Europe.

Like Fred, they are long-time migrants in their adopted countries and visit only occasionally.

OFWs indeed time their return usually on fiestas and Christmas holidays. But the visits of Julio and Fred came during the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, making them traumatic to their hometowns and instructional to cultural scientists.

Julio arrived in Abra on March 8, 2020, in time for the Kawayan Festival of the province, a weeklong event that had already started on March 6, recalled Abra Provincial Health Officer 1 Dr. Antonio Valera, who was tasked to handle his case.

He attended the festival and went shopping in La Union. While there, he visited a friend in a hospital.

Because of hospital protocol, he was tested for COVID-19 and was told that he was a person under investigation because he was already running a fever.

But Julio didn’t tell anyone about that and did what most OFWs normally did, attending his hometown party and another party in a nearby town.

Dr. Valera said that they only learned of it when the hospital in La Union told them of the positive result days later.

Julio would be the first COVID case in the Cordillera.

“He was responsible for infecting other residents, including his father,” Valera said.

Abra realized it was not prepared to handle COVID at that nascent time of the pandemic.

It didn’t even have a place to hold returning OFWs or even a facility to take care of positive cases.

Julio was brought back to a hospital in La Union.

While there, keyboard warriors and even his fellow Abrenians censured his irresponsible act.

“We were even thinking of suing him,” Valera said.

“And we thought the OFWs would learn their lesson, it turned out there were other similar cases in Abra after him,” he said.

One of the positive things from the Manabo seafarer case was that it made the provincial government come out with a localized surveillance system for COVID.

On March 15, 2020, then Governor Joy Bernos gathered the Association of Barangay Chairmen in Abra and told them that “you are all responsible for your constituents.”

She made them file daily reports about the travelers going in and out of their villages.

Throughout the pandemic and despite the severe lack of hospital and medical infrastructure, Abra maintained a low infection status.

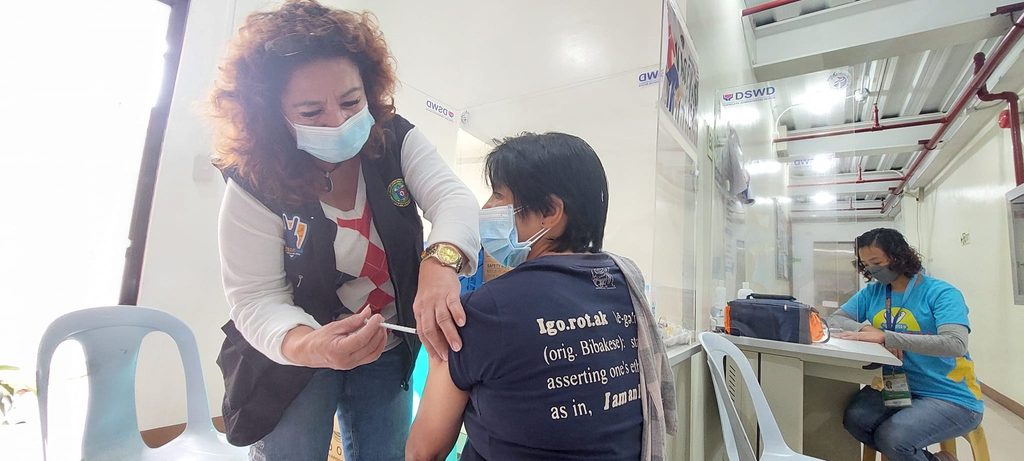

Its barangay network also helped it attain a high COVID vaccination rate.

Meanwhile, COVID was already raging in the country when Fred came home to Bontoc on December 14, 2020.

Cordillera already had recorded 8,500 COVID cases by that time, although Mountain Province still had one of the lowest rates in the country.

This was, after all, the province that shooed away Piolo Pascual and his group when they tried to sneak into Sagada in July 2020 to shoot for the SONA of President Duterte.

Some towns in MP and Kalinga also set up the traditional tengao (also te-er, seday, or ubaya where the boundaries are physically closed and no one can enter or leave the village) in the hope to contain the virus.

But no one can really contain culture.

During the holidays, Fred and his wife went around Bontoc and even as far as Sagada to meet up with relatives and friends.

It took more than a month before he was identified as the cause of the outbreak of the so-called UK variant of COVID in the province.

Although Fred had tested negative for the variant and his wife did not test positive, many of the variant cases in Bontoc were linked to him.

Five villages were placed under institutional tengao on January 25, 2021, by former Bontoc Mayor Franklin Odsey because of the incident.

Dozens were hospitalized after becoming positive for COVID, including Mayor Odsey, who attended a canao in Samoki with Fred.

Several of the elder villagers died because of the exposure.

In hindsight, Odsey said that they should have been less lenient in dealing with balikbayans, however important they are.

One other incident in the province showed how culture tried to take precedence over the virus and lost.

One is when then-Mayor Gabino Ganggangan of Sadanga announced on social media that he will ease COVID restrictions in his town last February 13, 2021.

His “Sadanga new normal” policy lifted lockdown restrictions and the two-week quarantine requirement for those entering his town. He said “su-ob” or steam inhalation and kalamansi would suffice.

Ganggangan said social distancing was unnecessary in his town because houses were far away from each other.

He was initially declared a hero on his Facebook profile with thousands of Cordilleran netizens applauding his bravery.

But only a few months later, he was hit by a virulent version of COVID that nearly killed him. Although he was able to recover, he died of a heart attack while attending a wedding in Bontoc on January 20, 2022. His long bout with COVID probably contributed to the weakening of his vascular system, his doctors said.

Like Julio and Fred, more than 7,000 Cordilleran OFWs returned to the region in 2020 when the country’s reintegration program ensued.

But unlike Julio and Fred, many of these Cordillerans cannot go back to their provinces.

Many are like Bridgitte Badando, employed as domestic help, but the pandemic resulted in their work termination and non-renewal of contracts.

For Bridgitte, her host family in Hongkong was thinking of migrating to Australia. They said they would contact her after having fixed their papers and she could follow suit. But since December 2020, she has not heard from them.

She applied for reintegration and said that she needed financial help but she barely got government support.

She has since returned as a food server, the same job she thought she would escape from when she went to Hongkong.

Badando is from Itogon in Benguet and she has let me in on her network of friends – all domestic helpers from Cordillera – still hanging on in Hongkong.

One of them is Gail, also from Itogon, who went home last April 2020, supposedly to attend the burial of her mother.

As it turned out she wasn’t able to attend the burial because her stay in the quarantine hospital in Tarlac took up most of her time and by the time she was home, her mother was long cremated.

She also cannot leave because she contracted COVID on the government bus going to Baguio.

To make it worse, she spent all her money and had to borrow from a relative for her fruitless trip back to Hongkong.

Vicky, another in the group chat, said that she was already fired by her boss and was already out of contract. But listening to her friends’ horror stories, she decided to try her luck.

She was able to get another nanny job in Kowloon but the pay was much less. Vicky said she will go home by December this year so she wouldn’t be seen as a failure in their village.

“They see us as heroes. It would be a shame if we come home looking like victims even if we really are. Ha ha ha,” said Vicky in Ilocano.

She said that there are many like her who are practically out of contract and taking advantage of the pandemic and the political upheaval so they can stay longer in Hongkong to earn.

She calls her status, makikigian or Ilocano for “staying in someone’s home.”

Vicky said she is more proud of helping her son graduate from high school back in Baguio.

“He shows me his modules through his phone and my other housemate and I would help in answering them,” she said in Ilocano.

We asked Deputy Speaker Kristine Singson Meehan, being the president of the Northern Luzon Alliance, about the situation of the OFWs in Northern Luzon and how they help in legislating reforms if similar COVID-like pandemics come our way.

She said that right now, it is the Inter-Agency Task Force that decides on the policies, and provinces and towns have to follow suit.

She agreed that OFWs and balikbayans come on different levels and are received differently by their hometowns.

Meehan said, for example, that she helped her province set up quarantine facilities and hotels as options for people that do not wish to stay in quarantine facilities.

“And from my discussion with hotel operators way back, they offered discounted prices for their rooms. It’s a much lower rate than usual as we are in a state of a pandemic,” she said.

“For OFWs from the information given to us, it is OWWA that assisted in providing quarantine facilities and hotel accommodation choices to OFWs. In some cases due to group arrivals, OWWA may have chosen accommodations to contain and isolate groups that traveled together. OFWs didn’t have to pay for their accommodation. OWWA guaranteed payment. But later their policy on that changed,” she said.

“In general during the pandemic, the guidelines kept changing as everything was new to everyone. The situation, too, keeps changing and government agencies and local governments have to adjust and be very flexible. The ever-changing guidelines and policies, too, led to the confusion of many,” she said.

But with COVID and other so-called new diseases, the OFWs and the balikbayans remain constant and confused.

In April 2003, the Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS), one of the first coronavirus diseases, infected an OFW, a nursing aide from Canada, on her way home to Alcala town in Pangasinan. She and her father were the only cases in the country and both later died while the whole town of Alcala was ostracized for a month.

A generation later, the country was hit by COVID-19.

And because of the ubiquitousness of OFWs and balikbayans, the country would be hit again by this new round of viral diseases.

Some will be like Julio and Fred who would unknowingly carry the disease and go on with their lives. There would be more Brigitte, Vicky, and Gail who will carry the hidden costs of the sickness longer than they can manage.

This story is part of the journalism fellowship of the Philippine Press Institute under the auspices of the Hanns Seidel Foundation.

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.